Photo by Oli Scarff/Getty Images

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2013/jan/11/johnny-marr-smiths-morrissey-politics-pop

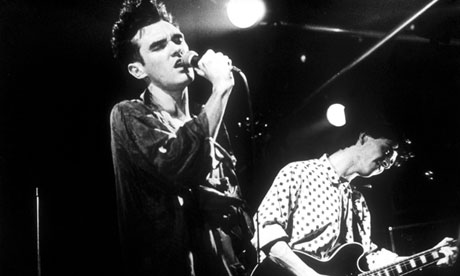

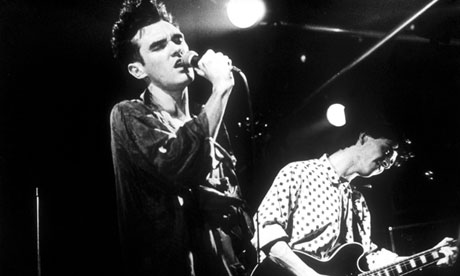

Morrissey and Marr onstage during the Smiths 80s heyday. Photograph: /Paul Slattery

Morrissey and Marr onstage during the Smiths 80s heyday. Photograph: /Paul Slattery

David Cameron, stop saying that you like The Smiths, no you don't.

I forbid you to like it.

I forbid you to like it.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2013/jan/11/johnny-marr-smiths-morrissey-politics-pop

Johnny Marr on the Smiths, Morrissey and putting politics back in pop

With the release of his first solo album The Messenger, the former Smiths guitarist talks about finally embracing his old sound, David Cameron and why he and Morrissey don't talk any more

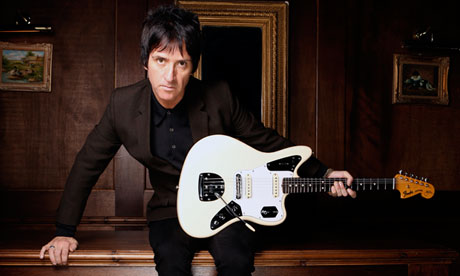

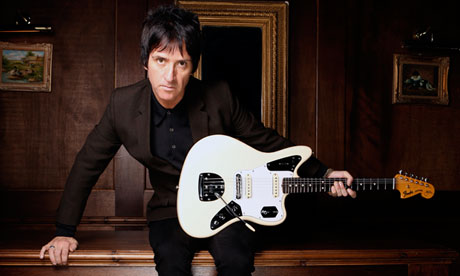

Johnny Marr: 'We invented indie as we still know it.' Photograph: Richard Saker

During the December 2010 debate over the raising of student tuition fees in the House of Commons, Labour MP Kerry McCarthy asked a rather surreal question of prime minister David Cameron, who had just gone public with his rather unlikely fandom of leftwing, anti-Conservative, seminal Manchester indie band the Smiths.

"As the Smiths are the archetypal student band, if he wins tomorrow night's vote, what songs does he think students will be listening to?"asked the member for Bristol East, to roars from the opposition benches. "Miserable Lie, I Don't Owe You Anything or Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now?"

Cameron, improbably, responded in kind. "I expect that if I turned up I probably wouldn't get This Charming Man," he quipped, "and if I went with the foreign secretary [William Hague] it would probably be William, It Was Really Nothing."

Reading this on mobile? See the video here

"You do wonder," comments Johnny Marr, drily. "What part of the Smiths ethos did he not get?"

Few British groups have had the far-reaching impact of the Smiths, and few guitarists are as celebrated as Marr. He was recently named NME's ultimate guitarist (ahead of Jimi Hendrix and Jimmy Page), and even has a Salford University honorary doctorate for "changing the face of British music".

"I get a lot of people being very nice to me, even when I don't want them to be," the former Smith chuckles, pointedly. "With one or two exceptions, the people who like the music are always super nice and don't want to bother you. They just want to tell you how much they love it." He is nothing if not grateful to have been part of a band who "mean so much to so many people", but admits there is a downside: "It can be difficult when it's raining and you're running for the train." His grin widens, but he adds, more seriously. "Or you're trying to move on."

Marr has spent 26 years trying to move on from the Smiths, who split in 1987, in which time he's been quite the musical chameleon. What he calls a "searching personality" has taken him from synthesizer pop with Bernard Sumner in Electronic to foreboding rock with Matt Johnson's The The, from folk with Bert Jansch to adult-oriented pop with Crowded House via playing with Bryan Ferry and Chic's Nile Rodgers. He has fronted short-lived Stooges-ish swamp rockers the Healers, enjoyed an unlikely US No 1 album with leftfield indie outfit Modest Mouse and taken his roving guitar gunslinger role to shouty Wakefield indie band theCribs.

It's hard to see how he could have journeyed further from the trademark "chiming man" guitars he played in the Smiths, short of playing a kazoo. Yet here he is, a youthful 49-year-old, talking about his first ever solo album, The Messenger, which sees him returning to the big tunes and unmistakable, cascading guitar arpeggios that made him the guitarist of his generation.

Reading this on mobile? See the video here

We meet in a London photographic studio, where, having his picture taken earlier, Marr still looked unmistakably the bouffant-haired tunesmith whose 1983 Top of the Pops appearance alongside a gladioli-hurling Morrissey provided indie rock with its "year zero" moment. His reputation as one of rock's nicest guys is not without merit, yet he is also savvy and single-minded, and when he agrees to the photographer's request for photographs with a guitar it's with a matey but firm: "Just don't tell me how to hold it."

In person, the matt black Keith Richards barnet and glittery nail varnish on his plectrum-holding right hand suggest a man who has spent his entire adult life as a national institution. Otherwise he's disarmingly normal, self-effacing but not falsely modest, and – mostly – open. But he sounds very much a man on a mission.

"I felt something was missing from pop," he explains of The Messenger's prickly energy and epic, romantic soundscapes, which handily coincide with the widely predicted return of the guitar to pop's forefront in 2013. "When you hit it right on guitars in pop, it can be vivacious and exuberant and shiny. I've fond remembrances of bands like Blondie. Without being retro, if I'm really in the mood for it, that's what the guitar is for me. If people say parts of the record sound like the Smiths, I'm OK with that because hopefully it's got the same exuberance."

The Messenger doesn't just nod to the Smiths. As he suggests, the wiry post-punk of bands such as Manchester predecessors Buzzcocks and Magazine is a major influence. The title track is electro pop. Marr (who first sang in the Healers, and worked on his vocals in the Cribs), notMorrissey, is singing. But for years, Marr wasn't "OK" with sounding anything like the Smiths. In fact, as he now admits, the band cast such a long shadow that his musical shapeshifting was an "entirely conscious" decision to avoid sounding like his former self at all. If he came up with a riff that sounded anything like the group, he'd "bin it, flick the Vs up at it". As for the innumerable occasions when other people moaned to him that Johnny Marr didn't sound like, well, Johnny Marr, "No one likes to be dictated to," he insists, combative edge starting to take hold. "If you've been put in a box marked 'jingle jangle indie pop blah blah' then it's your responsibility to break out of that, otherwise you're creatively dead. You might as well write your own tombstone, with diminishing returns." He finishes with a proud, defiant salvo: "Bernard Sumner used to have his head in his hands going 'Everybody's gonna blame me!' When I first played live with Electronic, I came out playing a synthesizer."

But by 2005, he had been through so many metamorphoses that he couldn't see himself as a UK artist any more. So he went to Portland in the US (initially to join Modest Mouse, before hooking up with the relocated Cribs) to "find some space to play". One night, his fingers found the beginnings of the sort of instantly melodious guitar shape he turned out by the truckload when he was the musical half of songwriting partnership Morrissey and Marr.

"In the past, I'd have shredded it because it sounded too much like me," he admits, "but it just felt so sweet and so genuine, it seemed important to just go with it." The riff became the Cribs's song We Share the Same Skies, after which he began pining for the way bands operated in the UK, especially in his youth.

Reading this on mobile? See the video here

"I knew I needed to come back to front a group that operated like that," he explains. "So we all live in Manchester and get together to rehearse a few nights a week even though we don't need to. I just started to act like I was in that group, even though I envisaged a solo record. I didn't want to be in a group where the lead singer didn't want to play guitar any more. So that meant I was the right man for the job." He sniggers. "Luckily!"

Marr denies that he's been stubborn, just single-minded. "It's the prerogative of a young man in his 20s and 30s to be on one," he considers of what seems a partial volte-face, admitting that having been in the Smiths leaves an awful lot of baggage.

"But equally, if you're in your 40s and still carrying that around, then you've got a problem."

In May 1982, Marr was an 18-year-old clothes shop assistant when he sashayed up to fellow working-class Irish-Mancunian and renowned misfit-about-town Steven Patrick Morrissey to suggest they form a group. The pair of them were so instantly infatuated with each other's possibilities that on their second meeting they planned the Smiths in detail. They plotted the label they would sign to (Rough Trade), the famous record sleeves, even the colour of the label on their debut single (blue). Everything came true.

"I didn't expect that. I'd written a load of catchy tunes in my bedroom."

Morrissey and Marr onstage during the Smiths 80s heyday. Photograph: /Paul Slattery

Morrissey and Marr onstage during the Smiths 80s heyday. Photograph: /Paul Slattery

While Marr's guitar style and worldview assimilated Motown, Chic, the Hollies and Iggy Pop, Morrissey added words steeped in Oscar Wilde and 1960s kitchen-sink drama. Morrissey's declaration of celibacy was another genius move, which made fans desperate to be the first to love him.

"We invented indie as we still know it," says Marr, the debt ceremoniously acknowledged in the 90s when Oasis's Noel Gallagherplayed Marr's guitar.

But the guitarist was equally taken aback by the reach of the Smiths' non-musical impact: the amount of people that turned vegetarianbecause of Meat is Murder, or became politically motivated through Margaret on the Guillotine. "We were of that generation that came after punk and post-punk," he explains. "We're grateful for the revolution, but there was a bit of homophobia there, and sexism. There wasn't in indie. People don't talk about it now, but it was non-macho. If you were an alternative musician, you were political, because of the times [Thatcherism and the Falklands war]. It was taken for granted that the bands you shared a stage with had the same politics. I'm not sure you could say that now."

So when David Cameron started saying that he loved the Smiths, Marr's old political edge – and sense of mischief – was suddenly revived, and he issued a now famous tweet: "David Cameron, stop saying that you like the Smiths. I forbid you to like it." It went viral."I got a lot of support," he grins, of what was primarily a joke. "But I didn't realise Twitter was a forum for so many angry people. I'm amazed how many people who should know better were so reactionary towards me. 'Hey Johnny Marr, I'm no Tory but where do you get off on forbidding people liking your music? I bet you won't give Cameron back the £10 he spent on The Queen Is Dead?' What are you talking about?"

Marr may have copped flak, but the incident was an early example of how Cameron – an old Etonian who also professes to adore the Jam's coruscating The Eton Rifles – can be light on detail.

"I know. I seriously did not like him dropping our name. He picked the wrong band."

Marr was equally taken aback – and thrilled – when at the student protests over the raising of tuition fees, one young woman was photographed standing over riot police in Parliament Square, wearing a Smiths Hatful of Hollow T-shirt, an image that until recently featured on his homepage.

"I thought it'd been Photoshopped," he admits. "It took a few minutes to sink in that it was real. But I ended up giving it to everyone then. Clegg; the Queen. I was off!" He chuckles.

Marr's amusement turned to surprise when Morrissey joined in the kerfuffle, issuing a statement supporting his ex-bandmate's tweet about Cameron. It was the first time they had united publicly on anything since the Smiths. However, while Morrissey is something of a dab hand at controversial statements, they didn't discuss it. "We used to, back in the day, for the bedevilment of it."

In fact, Marr reveals that while the two former confidantes were meeting up occasionally a few years ago, nowadays they no longer speak at all.

"We don't have any reason to, to be honest," he says, with a touch of glumness. When Marr remastered the Smiths' back catalogue two years ago, he emailed Morrissey (along with all his ex-bandmates) saying he could hear the love in the music, but didn't hear back. "It was a nice way to leave it, I think," he considers, tiptoeing carefully around too much discussion of his former partner. "You can only try and be friendly with someone for so long without getting anything back. You just think: 'Ah, fuck it.'"

When Marr started Electronic with Bernard Sumner, Morrissey opined: "He's replaced me. I'm not sure what with." Does Marr think he still feels betrayed? "You never know. I don't have any weirdness about it, or any of them."

Marr – whose exit precipitated the split – has long found himself being blamed for the Smiths' demise, calling a meeting after finding himself exhausted through writing the songs, (latterly) producing the records and running the unmanaged group's business affairs. Some months before, a sign that not all was well with the guitarist (who in those days coped with the pressures by drinking heavily, unlike the teetotal, running-and-white-tea regime he adopts now) came when he drove his car into a wall and was lucky to escape alive. But it has long intrigued me – when he called that meeting, did he know that he'd come out of it a former Smith?

"In all honesty, I don't think I did. We just needed a reset, to do things differently. Two weeks' holiday would have been nice." But Marr has no regrets: he's proud that the Smiths did everything at the top of their game. "I'm glad I didn't spend 35 years in the same band. It's just not me."

Any lingering notion of the Smiths as a close-knit gang was finally demolished when drummer Mike Joyce sued the two songwriters over royalties. Marr still sees Andy Rourke, a friend since childhood, and the bassist dropped into the studio during recording of The Messenger. But discussion of the Smiths remains off limits. "If we need to think about what went on in the Smiths then we can torture ourselves by reading those books," he says, referring to the expanding pile of Smiths biographies.

There's just one thing that does get Marr's goat – the continual rumours that the Smiths will reform, which he accidentally fuelled himself recently when he joked that he would reunite the band "if the coalition government stood down".

Reading this on mobile. See the video here

"Some guy stuck a camera in my face," he explains. "If I don't say something glib, what else is there to say? 'Fuck off!'? It would have saved me a lot of trouble." He suddenly sounds truly weary. "But then that becomes the story."His irritation doesn't last, and he's soon excitedly remembering how watching Bert Jansch work at close quarters convinced him he could be a solo artist, even though he does indeed have a band, who rehearse in Manchester a few nights a week. Just like you know who. Writing songs is very different to how it was with Morrissey – who would add words to a tape of Marr's music and return it, which could often result in a completely different song to how Marr imagined. "That was a fascinating process." But he's now enjoying "a sense of liberation, being able to call the shots" and sing about his own concerns, whether humanity's relationship with technology or, on the sublime, autobiographical New Town Velocity, the day, aged 15, he "left school for poetry" and tore around Manchester celebrating his first taste of freedom.Around a year ago, Marr included a couple of Smiths songs in a live set at two low-key gigs in Manchester, and was surprised how much he enjoyed playing them. While Morrissey recently announced plans to retire, Marr says he never will. But if he seems happy in his own skin it's because of a union that goes back much further than the Smiths.

As a little boy, while others had toy cars or teddy bears, Marr had a toy guitar. "Recently, my parents redecorated the house and there were a couple of my really old toy guitars knocking around. So they moved them out, decorated, then put them back, as if they were houseplants."

So when he was recently invited to speak at his kids' school, his wife, Angie, told him not to "terrify" them but to talk about what he knew. So Marr talked about being a guitarist.

"I said: 'If you want to be happy, find something you're good at and make it your life, whether it's being a train driver, architect, or whatever.'" He smiles as he lugs his trusty axe into a waiting car. "There's a lot to be said for being an expert at something."

No comments:

Post a Comment