Will Oldham

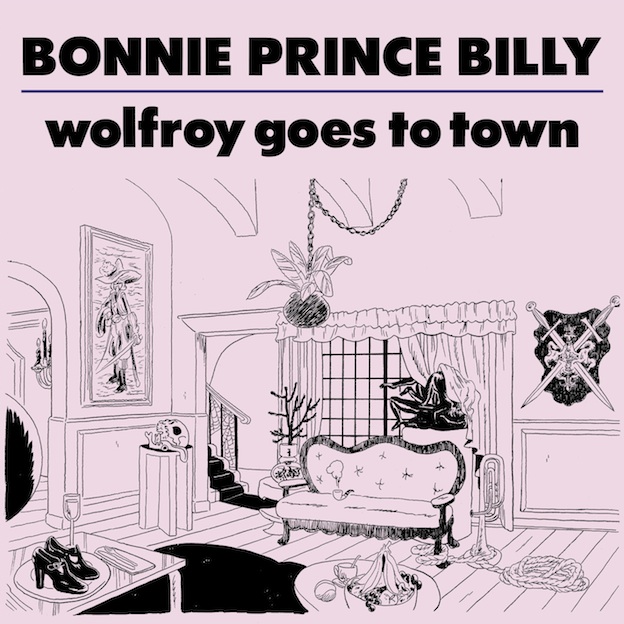

The enigmatic singer-songwriter on his new LP, Wolfroy Goes to Town.

By Mike Powell, October 10, 2011

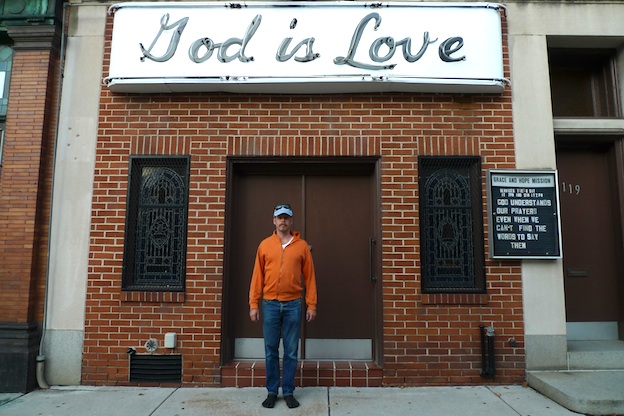

Photo by Jesse Fischler

Between studio records, singles, EPs, live albums, and compilations, Will Oldham has appeared on over 50 releases since the early 1990s. His earliest albums-- under the Palaceumbrella-- were stark, vérité recordings of folk- and country-influenced songs played by people who sounded like they were still figuring out how to hold their instruments.

In the years since, he's evolved into a strange and unprecedented kind of artist: on the one hand, an emblem of stripped-down, straightforward indie-Americana, on the other, a self-occluding songwriter who built a career out seemingly disconnected whims. He rarely records with the same group of players twice, he's changed his name multiple times in the past 20 years, he's appeared in art-house films and Kanye West videos. He has set up tours for the stated purpose of introducing bandmates to the state of Florida. Last year, he was ostensibly his own opening act.

The business world would not accept someone like Will Oldham: weak brand integrity, too indirect. I've experienced his career as a lifer (Lost Blues and Other Songs, age 16), though he's said he aims to reach a different audience with each album. His new one, Wolfroy Goes to Town, came out last week. It's friendly, slow, and spare. Like all of his work over the past five or six years, it feels like a half-turn away from what came before it-- a new stage with a familiar scene, or vice versa. There was nearly no promotion behind it, and he said that our interview was the only one he'd be doing. We spoke early on a Saturday morning, fixing coffee in different time zones.

Pitchfork: I hear music. Is there music playing where you are?

Will Oldham: There is. It keeps the voices quiet in the head, you know? I'll turn it down.

Pitchfork: What you were listening to?

WO: I use a digital music player-- we don't have to name brand names-- and constantly put things onto it, since there's not necessarily any dependable quality radio. I put things on it that are super meaningful or fun or inspirational to me as well as things that I'm wanting to familiarize myself with. And I find that when music catches me off guard, that's when I'm most open to it. So I play it on random. I thought it could be a nice thing to have going on to stimulate conversation while I was speaking with you.

When the phone first rang, it was this Polynesian style of singing that is insanely exuberant and powerful and has been utilized in hymn singing-- I don't know if it existed prior to Christianity coming to Polynesia. And now Frank Sinatra is singing "One for My Baby (and One More for the Road)". Do you listen to much Frank Sinatra?

Pitchfork: For a long time I had an uninteresting prejudice against him for reasons that weren't related to his music. But certainly whenever I have been drinking and people put on Only the Lonely there's something magical and despondent about that music that I like.

WO: Yeah, this is the last song on Only the Lonely. I like a lot of Frank Sinatra, but that record stands apart as this strange obelisk of musical complexity and loneliness. That's a record that has compelled me since my folks owned it, since I was 10. It still does.

About three weeks ago, I was trying to unlock some things about why it is the way it is, and I was reading a book called Sinatra! The Song Is You, which is about his approach to recording and performance. They talked about how at one point during the recording of that record, he stepped away in order to make a movie called Kings Go Forth with Tony Curtis and Natalie Wood. And I thought, "Oh, I'm going to watch the movie and it's going to help me understand this record." It was interesting and wild because he's the protagonist, but he doesn't get the girl and he loses his arm. So at the end he is an armless guy who's lost in love. Maybe it's another piece of the puzzle, but it certainly doesn't solve anything for me.

"Frank Sinatra's never been handsome, but he's one of my favorite singers. Who needs looks when you have a voice and power?"

Pitchfork: I have not heard of that movie.

WO: It's a sleeper. Its reputation has not gone forth as king's should have. Sinatra totally romances Natalie Wood's character and then Tony Curtis comes along and steals her away. And that's the end of the story: They don't get back together.

Pitchfork: Tony Curtis does seem more savory in that face-off.

WO: It's true. Frank Sinatra's never been handsome; I think his looks are off. There was a year or two where his weight and the state of his hair seemed to gel well with what genetics have given him. But for the most part he always seemed like a strange specimen of humanity. But he's one of my favorite singers. Who needs looks when you have a voice and power?

The Wolfroy Goes to Town band: Oldham, Danny Kiely, Ben Boye, Van Campbell, Angel Olsen, Emmett Kelly. Photo by Dirk Knibbe.

The Wolfroy Goes to Town band: Oldham, Danny Kiely, Ben Boye, Van Campbell, Angel Olsen, Emmett Kelly. Photo by Dirk Knibbe.Pitchfork: At this point, I feel like you put out a record every year but it always feels unexpected when it arrives.

WO: Yeah, for me as well.

Pitchfork: Are you of the "I know not what I do" mentality?

WO: I think so. Sometimes it's daunting or exhausting to be in that state, so I try to make inroads toward knowing. But usually it feels like the majority of thought processes and actions come as a surprise-- that the world is a pretty new place on a daily basis. But whenever I can get a handle on any sort of regularity or something that could be deemed wisdom, I'm very grateful for it.

Pitchfork: The author Barry Hannah has said that he likes to write from a first-person perspective because he feels like the concept of wisdom is often false-- people think they know something, but, in reality, there is no ultimate truth and you're just piloting through with what little you understand.

WO: Yeah, I've gotten a lot of strength from that concept over the years. At the same time, you don't want to be blindsided at some point because you've taken too much comfort from knowing nothing. So you try to keep a little store of practical knowledge. At a certain point you have to pretend that something is true in order to have a relationship with the world.

"A record is something that isn't real or true. It's like cinema. It's a construction of something hyper-real and surreal and unreal all at the same time."

Pitchfork: It's a comforting thing. Since you deliberately don't promote your albums beforehand, I got one of those watermark CDs from Drag City that has like a little skull and crossbones on it but I know nothing about Wolfroy Goes to Town. It gives me a very exciting chance to be able to ask you 90s questions like: Where did you record it? What is it? Who plays on it?

WO: Well, [guitarist] Emmett Kelly and I have worked together now for almost six years now, starting with The Letting Go, and a lot has happened in that time. At one point we made theBeware record together in Chicago. We made it in a proper recording studio and lots of folks were involved with it. But it was almost a denial of a lot of the things that I viewed as progress in the previous record, Lie Down in the Light. And though I truly love Beware, I wasn't sure why I went so far in in a direction that's opposed to my nature in terms of making a record. I like the result, but it's not sustainable, to use a catchword of the day.

So Emmett and [violinist] Cheyenne Mize and I went to this little room I have in this little house in Louisville and made the Chijimi EP. To me, that was the absolute in terms of how recording should be done. There were just three of us, no recording engineer. And it was done very quickly, so the energy of the record is based on our communication with each other and our chemistry, which is why I like records where the songwriting is done before the session. That way the two things that pop out when you're listening are the captured performance and the communication between the musicians based on what the songwriter has given them.

Then Emmett and I returned to that room to make The Wonder Show of the World and in some ways pared it down even more. Most of the time it was just he and I in the room, thoughShahzad Ismaily came and played bass while we tracked the basic parts of the songs. I wanted to carry forward with this magical room. One constant mistake I've made over the years is leaving one recording session and thinking that I know something about how to make a record and then trying to repeat it. It never comes out. The feeling and the music is not the same because it ignores the fact that time has passed. Part of the success of one event is based on it being unprecedented.

So here we go to make this record in the same room, and I had to tweak the formula somewhat. We had this group of people that we assembled for last December's tour of the Kevin Coyne and Dagmar Krause record Babble. It was so great playing with this group of musicians-- three of them are based out of Chicago and three out of Louisville, so it had this nice balanced energy to it-- that I thought I would bring this new group of songs to them. We'd go into the magic room, the poor shelter, and make a record, bringing in Shahzad again as our extra energy, to be a creative and technical advisor. We made it in late spring, early summer of this year, and we came into it with 12 songs that we had played once in Chicago at Millennium Park. When we got into the session it felt as if maybe two of them were outsiders, so we excised those and had a collection. That's my story. That's the record. [laughs]

Pitchfork: Where would you say this album falls on the spectrum you were talking about, is it more spontaneous or studio-oriented?

Pitchfork: Where would you say this album falls on the spectrum you were talking about, is it more spontaneous or studio-oriented?WO: When we first started to record, Shahzad was trying to capture the songs in this very natural and real way, but I feel like that's a denial of what making a record is. A record is something that isn't real or true. It's like cinema. It's a construction of something hyper-real and surreal and unreal all at the same time. You make a space that doesn't really exist. One of the big joys of being in this line of work is building the recorded versions of the songs.

That said, the idea is to only give some initial instruction: "OK, let's play. Ready? One, two, three, go." Then we see what happens. Instruction is only given after. We'll learn from each other-- that's why you have individuals in the room.

Pitchfork: Listening to those early Palace recordings, there's a looseness, but it feels like you're almost deliberately figuring it out while it's being documented. But if you listen to something like Lie Down in the Light, the players are just socapable. If you had access to those sorts of people in the early 90s, would you have made something of it or were you deliberately doing what you were doing because you believed in that approach?

WO: I think that's too much of a hypothetical, because not only did we not know how to make a record, or necessarily how to write a song, but we didn't know that this access was evenconceivable. I didn't understand session musicians until I took the Master and Everyonesongs to [Lambchop's] Mark Nevers in Nashville, on David Berman's recommendation. We were looking for something to complement what my brother Paul and I had done in the performances, and Mark said, "Let's call the Singers Union and get a female singer in here, and I'll look in the yellow pages and find a cellist." These people came and I was like, "What the hell? What's going on here? What universe is this?"

"For a long time I've walked through this world with the desire, like in Rear Window, to look into other people's lives because I know that there is a way in which I am the same as so many of the strangers that I see."

Pitchfork: For what it's worth, my favorite songs on the new album are "Black Captain" and "Time to Be Clear". I'm not sure why.

WO: It cheers me to hear about any songs being brought up individually. Unfortunately, it's not a tired or irrelevant metaphor when people talk about songs being like their children. It's like, "I liked Little Tommy-- he was great in the school play." And I'm like, "Wasn't he so good as the fig?"

Pitchfork: Is it Angel Olsen that sings that incredibly beautiful and surprising break in "Time to be Clear"?

WO: Yeah, right, what the fuck?! That was one of the things that came from our live arrangements, but what she did there in the magic room-- I was like, "Oh, my god." When something like that happens, I don't know how to feel. It's almost like I get hollowed out and then filled, but I don't know what it's with. It's a mixture of apprehension and satisfaction at the same time. "Time to Be Clear" is really just a stab to get that very influential Scientology demographic. [laughs] They'll be standing in line to buy this record yelling, "See!"

Listen to an exclusive solo demo of "Time to Be Clear":

Pitchfork: But what was the real idea with this album? Is there a unifying concept?

WO: That's something that usually takes me at least a year to be able to understand. To a great extent, I want to be the audience. When I listen to the music I love, there's a lot of faith and trust involved. I hear a song for the first time, or for the 10th time, and I think, "I love this song and I'm not going to try to figure out why I love this song but I trust that I know this song is going to give me something for many listens to come." My hope is that that translates into the music that I've been a part of making. I don't want to know everything. I've worked on it long enough that I still want to have this honeymoon period with the music. I do know that there's something beyond the initial impact of the song. There's something that I'm going to be able to perform in one year or five years, and maybe after performing it a certain number of times and thinking about the record, I will start to understand why it is what it is. I hope that doesn't sound lazy, because I don't think of it as lazy. I just think of it as me trying to have as much fun as possible and be as mystified as possible, but responsibly mystified.

Photo by Cairo

Photo by CairoPitchfork: There's something that unifies your records and yet each one has a different intent or idea behind it.

WO: My hope has always been that each record could have its own audience. Of course, it's awesome to have a cumulative audience for more than one record, but I like the idea that there could be a record that an individual might like and say, "I don't really want another Bonnie 'Prince' Billy record. I like this record and I like my Carole King record and I like my Dead Kennedys record."

Pitchfork: Do you imagine the ways in which a record like this would connect with people, or who it would be connecting with?

WO: No. For a long time I've walked through this world with the desire, like in Rear Window, to look into other people's lives because I know that there is a way in which I am the same as so many of the strangers that I see. Oftentimes I just think of making music as a way of illuminating those connections. You don't know. That's the thrill of making a record-- to see. I don't have to walk anonymously by this corner anymore because the man on this corner and I have a deeper connection that we didn't have a way of addressing before. I know for a fucking fact that I am not alone and sometimes everybody feels alone but we have to know that we aren't. And rather than giving that responsibility for assuring us that we are not alone over to the incapable hands of organized religion, let's do it ourselves and say, "What's the connection?"

Pitchfork: That's an inspiring and generous thought.

WO: And yet it's very selfish. But some people are good at it, especially people who are not Type-A personalities, or people who might listen to music as a way of connecting because we are incapable of asserting ourselves.

Pitchfork: Your music is presumably you and it's not you-- it's not a direct representation of who you are as a human being and your personal life. But do you feel like that's the effort: to reach out to people because you otherwise don't have the inclination or the capacity to?

WO: Yes. But the record itself is an example of what I'm talking about. It's wanting to reach out to Emmett and Angel and Ben and Shahzad and Danny and Van and to Sammy Harkham, who does the cover art, and to everybody at Drag City. We're doing this in order to relate to each other then by extension putting it out there to try to reach out to a bigger each other. We're hoping for financial reward in doing so, because that will allow us to do it again. So it's never, quote, "altruistic" because we do need to be paid, because that's what we've chosen as our job. We've chosen communication; communication is our job.

Artists: Bonnie "Prince" Billy, Will Oldham

No comments:

Post a Comment