INTERVIEWS

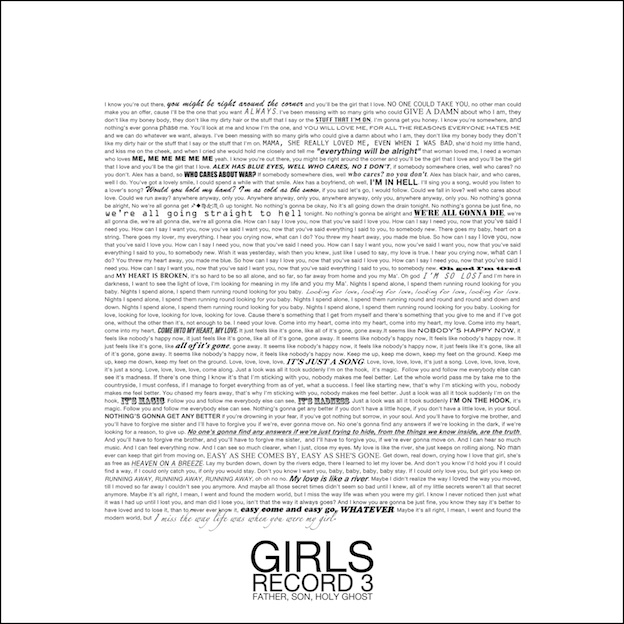

Girls

Leader Christopher Owens on the stunning new LP, Father, Son, Holy Ghost.

By Ryan Dombal, September 13, 2011

When I call Girls frontman Christopher Owens, he's bedridden for the third straight day. What's wrong with him? "Well, there are a lot of things wrong with me," he says with a chuckle. But he's not kidding. The singer-songwriter is in the thick of a self-imposed pre-tour drug withdrawal.

"I struggle with an addiction to serious, very heavy opiates," he says later on in the conversation. "Getting rid of this shit is literally the worst hell you can imagine. I don't know why I always go back to it, but I do." The admission isn't as surprising, perhaps, as it should be-- the 32 year old has made a point to keep his music and his life as honest as possible, even if that means telling strangers about his darkest addictions. This openness is inviting, though, and it's all over Girls' strikingly unguarded songs, which tell of love and loss with the wide-eyed naïvteté of someone half Owens' age.

By now, the singer's eccentric back story-- he was raised in the well-meaning but ultimately dangerous and perverse Children of God religious cult before breaking away and subsequently being taken in by Texas artist Stanley Marsh 3 -- is something of indie rock lore, and Owens doesn't back away from it. Several songs on Girls' new sophomore album, Father, Son, Holy Ghost, deal with Owens' fraught and complicated relationship with his mother, who allowed another son to die of pneumonia because of Children of God's anti-medicine stance and prostituted herself in Owens' presence while he was growing up. (She has since left the cult as well.) When he sings, "I'm looking for meaning in life, and you my ma," on the new record, you can hear the confusion of his experience as well as universal empathy.

Featuring warm, tuned-in playing from Girls co-founder Chet "JR" White on bass and on-and-off guitarist John Anderson, the new record expands Girls' referential sound with heavy metal riffs, classical guitar, lighter-ready solos, and belted-out gospel back-up vocals. And at its core is Owens, wonderfully wounded, hapless, and hopeful all at once.

Pitchfork: There are some very talented gospel back-up singers on Father, Son, Holy Ghost, and when you contrast them with your relatively small voice, it can sound...

Christopher Owens: ...funny! I know what you're talking about, and it's part of my neurosis. I was very much aware from the first recording we did that my voice sucks. It's fun to perform and be a singer, but writing songs is what really makes me happy. While we were recording this album I sent a Tweet to Justin Bieber: "Hey Justin, I'm the lead singer of Girls and you should come be the singer in our band. It'd be great for your career." Imagine that-- he'd be like the new Julian Casablancas ! I'd give him all my songs and he'd sell millions of records. He would do a better job on vocals and I would be happy watching the shows from the side and writing songs for him. But he never replied. I knew he wouldn't, but I was dead serious. And what I was acknowledging with the Tweet was that everything on this album had jumped up in quality except the singing. But those are the breaks, man.

Pitchfork: Your voice might not be Bieber-level, but I think it's improved a lot. On your first album, it sometimes sounded like you were making fun of your own voice while you were singing.

CO: I was. [laughs] On that record, I was really self-conscious about some of the lines. Like how I say the first line of "Lust for Life" in this snotty voice: "I wish I had a boyfriend." When I hear it, I don't even think it's me sometimes. If you listen to Ariel Pink and John Maus, when they say some line like, [sings in low tone] "I've finally found the one," they do it in a fake voice, almost like they're pantomiming it. It's the vocalist as an actor. You make fun of the lines. Other people do it. Nick Cave does it when he talks about murdering a woman in a song.

Pitchfork: Do you think it's a cop-out to do that theatrical voice?

CO: Yes. That's why there's less of it on this new album-- I have more confidence. I've never written a disingenuous song. They're always written during a breakdown or some overwhelming moment; my cup overfloweth, and there comes the song. But there is the self-conscious thing about knowing that I'm not as good of a singer as Elvis Presley.

"While we were recording this album I sent a Tweet to Justin Bieber: 'Hey Justin, I'm the lead singer of Girls and you should come be the singer in our band. It'd be great for your career.' Imagine that-- he'd be like the new Julian Casablancas!"

Pitchfork: You mentioned Ariel Pink as an influence, which is funny because I feel like you are opposites in a lot of ways when it comes to songwriting. You're direct, and he's not.

CO: Ariel Pink is a cornerstone in my foundation because he lit my fuse, and that's absolutely invaluable to me. Now, I gather inspiration from a lot of other places-- if I just copied him, that would be horrible. I've only copied him a couple times. [laughs] But we're not alike in any way, shape, or form. Ariel is the mad genius and the best songwriter of our time, but there is a place for me somewhere pretty high up there-- I'm pretty damn good. But Ariel's also on a different drug than I am. I'm a junkie; that guy's up all the time, bouncing off the fucking walls.

Pitchfork: As far as your singing, you seem to simply be trying harder on this record, too.

CO: I'm going for it, yeah! [laughs] As I was writing "Love Like a River", I could hear Beyoncé singing it, and it was beautiful. If she would do it, it would be a fucking number one hit, I guarantee you. But she'll never speak to me, and she'll never do it. She doesn't know I exist. It was a challenge for me to sing these songs but, at the end of the day, it's like, "Oh fucking well." You just do it.

One of my heroes is Randy Newman. He writes these amazing songs that people cover-- when Nina Simone sings "I Think It's Going to Rain Today" you want to cry. But even when Randy Newman sings it and his voice is obviously bad, you still say to yourself that it's a fucking knockout song.

Pitchfork: I thought the last song on this album, "Jamie Marie", sounded a lot like Randy Newman, actually.

CO: You caught that? Yes! I even sang like him on it. Each song has a different celebrity name attached to it-- when I go to the studio with JR, I say, "This is a so-and-so song." I'm not going to give away who they all are, but "Jamie Marie" is the Randy Newman song. The great thing about Randy Newman is he just says whatever the hell he wants. I copied him, man. It's cool. I want people to know those things.

I love this songwriter named Lawrence Hayward, and he had a song where he sings, "And what I've got to say isn't new/ So I'll use this old tune." It's about how all of us are just copying each other because we love each other and we want to be like each other. You read something like Life, the Keith Richards autobiography, and he just wants to be like various guys. And they all want to be like the Everly Brothers. It all goes back to the Everly Brothers.

"As I was writing 'Love Like a River', I could hear Beyoncé singing it, and it was beautiful. If she sang it, it would be a fucking number one hit, I guarantee you."

Pitchfork: I feel like a lot of artists might scrap something if it was too reminiscent of another artist or song, but you embrace it.

CO: My whole approach from day one has been to be honest. It's been disastrous to talk about my past and drugs in interviews, but it's honest. It's also been a good strategy for me, because it means I'm never at a loss for words.

Pitchfork: Sonically, this album sounds so much richer than your first one. How much of a goal was it to step things up on the production end?

Pitchfork: Sonically, this album sounds so much richer than your first one. How much of a goal was it to step things up on the production end?CO: This really is the album that we would have made as our first one if we could have, as far as the production value. We would have worked in a studio with better equipment and we would have hired back-up singers instead of me trying to do it. Like, at the end of "Hellhole Ratrace", the back-up vocals are all me. They worked at the time, but I know they sucked. But nothing else has changed. I mean, there are some songs on the new album that are older than ones on the first album.

Pitchfork: Which ones?

CO: The heavy metal song "Die" is one of my first-- once upon a time, Fleetwood Mac were a heavy, blues-rock London guitar band and they had a song called "Oh Well", which is the direct influence on "Die". Plain and simple, it comes from really liking that song. JR and I used to play the "Die" riff for long periods of time on opiates until one of us would fall asleep. We dreamt of the day we'd properly record that song.

And I wrote "Vomit" so long ago and I believed in it so strongly. There was a few times where people thought, "I don't know if this is a good song for this album." But then we recorded it and everyone's mind was blown.

"I think about the Bible in a completely different way now.

For example, I like Jesus very much-- he was one of the first rock stars."

Pitchfork: Why did you name that song "Vomit"?

CO: Well, it's about an obsessive, unhealthy need for co-dependency. I wrote it because my girlfriend at the time would go out constantly and never invite me or tell me where she was. I would literally go around town, [sings] "Looking for you, baby." I played her that song one night and she was like, "Aw, you poor guy." And I was like, "Fuck you." But that was not a time of my life I was proud of. That relationship failed because I was immature. Try landing in San Francisco from podunk Amarillo and not knowing anybody, then you meet the coolest girl in town, go out with her for two years, and suddenly she stops talking to you. You're living together but she's never home. It's unhealthy; I didn't need that. I should have been like, "I don't want no scrubs." But I didn't and I was whining this Nick Cave whine, like, "Isn't the way I whine grand?"

But, as far as the title "Vomit", in the Bible there's a book called Proverbs which is written by King Solomon, son of King David, during the time when the Kingdom of Judea was at peace and flourishing. King Solomon was known for his great wisdom and he also fancied himself a poet, a songwriter. He wrote this verse that goes exactly like this: "As a dog returns to his vomit, so does a fool return to his folly." So, to me, "Vomit" is about me, the fool, returning to his folly. This girl is mean and she doesn't want me anymore, but I was like a dog returning to my vomit every time.

MP3: Girls: "Vomit"

Pitchfork: Last year, you did a Pitchfork.tv session in a bathtub where you played three new songs that aren't on this record, and I'm always reading about how you write songs constantly. Was it hard picking the best ones to include onFather, Son, Holy Ghost?

CO: I could list 20 more songs that could've been on this album, but it's better that they're not. We did talk about making a 20-track record, but we had to stop because we couldn't pay for more time in the studio. But there's [another] album which is all written-- the songs that I played in that bathtub are numbers three, seven, and eight on that album. They go together, so they couldn't be on this record.

Pitchfork: How far in the future do you have these releases planned out?

CO: I'm planned very far in advance. [laughs] But I'm also flexible. For example, I do have a serious, strong plan to make a country album at some point. And I've been writing instrumental songs on my classical guitar-- there's a time and place for that, which is far in the future.

I have 83 songs that have not been recorded. So that's a lot of work sitting around waiting to get done. There are moments of frustration when I'm on the road and I'd rather just be making these songs. But you need to give people a break.

Pitchfork: Based on your Twitter, you seem to be interested in a lot of teenage singers and stars. What is it about those people that is appealing to you?

Pitchfork: Based on your Twitter, you seem to be interested in a lot of teenage singers and stars. What is it about those people that is appealing to you?CO: It's a natural attraction. But I've been a Dakota Fanning fan since 2003, and she was a child then, so it's not because she's a teenager. If people are cool, I like them.

But it's very true that my teenage years were robbed from me. I don't have a grudge, though. I've gained wisdom from it. Like, I learned to read not from going to school but from memorizing passages in the Bible, which is beautiful, old Shakespearean English. That's a good education. But I did pretty much just freak out in my teenage years because they were oppressive.

"I thought Father, Son, Holy Ghost was an epic title for an epic album."

Pitchfork: Do you get different things out of the Bible now than when you read it when you were younger?

CO: Oh yes. I read it for fun now, and I like it very much. I think about it in a completely different way. I like Jesus very much, for example. I think he was a neat guy. I look at his words and actions in conjunction with the ideas of the Old Testament, and he was one of the first famous radicals, one of the first rock stars. Jesus was cool, everybody knows that. But there was a time when you could've told me anything interesting about Jesus, and I would've put my fingers in my ears and said, "Shut up, fuck you."

I had a big block of years where I was very angry, and I had a very bad association with Children of God. If I kept that attitude, I probably would have committed suicide by this point. I was very truly depressed. But I met a man named Stanley Marsh 3 and my relationship with him encouraged me to be positive and optimistic. He was basically the person who was like, "I think what happened to you is very neat," and he would explain why. He made me feel very good about myself. I will be indebted to him for the rest of my life for that and a million other reasons.

I have this movie I watch anytime I get too depressed. It's called Brother Sun, Sister Moonand it's about St. Francis' life. He was another famous dropout, a rich kid who gave up all his goods to become a beggar because of the ideas presented in the Bible. There's a verse that says, "Consider the lilies of the field. They spin not, neither do they sew, yet Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like these." It's about simplicity. It's a Zen idea.

I watch that movie because it's very beautiful. It's made by Franco Zeffirelli, who's a fabulous Italian gay that made wonderful pictures about the Bible. I like everything he's ever made. He's still alive and asking the Pope if he can be a stylist, from what I last heard. Most of his movies were about religious themes because he's an Italian Catholic. Without ever saying it to you in open language, he presents this idea: "I can be gay, maybe even an atheist, but still love these people and this history." That's how I feel about it.

Pitchfork: Titling your album Father, Son, Holy Ghost is pretty audacious. Did you have any reservations about it?

CO: No. The one thing I didn't want people to think is that it's some reference to the Children of God, like, "Ah, yes, finally, a reference to the torturous childhood." It's not that. In churches, you repeat these phrases, and they become very key. But that wasn't the kind of lingo we used in the Children of God. We said, "I love you, brother; I love you, sister." We just read the Bible, and then talked very normally to each other. It was very anti-church, very much just people living together and being good to each other, essentially. Things got out of control, I guess.

To me, Father, Son, Holy Ghost is an idea of the presentation of something's origin, something's identity, and something's spiritual quality. I thought it was an epic title for an epic album.

"So many people wait around for somebody to say 'I love you.' But sometimes it's just as much fun to love somebody that doesn't even think about you."

Pitchfork: On songs like "Honey Bunny" and "My Ma", you talk about your relationship with you mom, who brought you up in the Children of God, really frankly. Was that difficult?

CO: I am in a healing process with my mom. We're both very friendly, and we've talked for a long time. We've never been angry at each other, but there's been very dark elements in our relationship. There are a few efforts on this album to address those things. I think the reference in "Honey Bunny" is a very beautiful and positive one that will help her feel not so bad. Because she feels bad, she really does. And "My Ma" is a song about admitting that I need her: "I'm looking for meaning in life, and you my ma." It's like saying, "I've acted rebellious, and I left on my own, and I didn't talk to you much, but I really would like to get back together." And we're doing that-- we just visited and it was very nice. The references are a very realistic vision of the healing process occurring between her and me.

Pitchfork: Obviously, most people can relate to having troublesome relationships with their parents, but at the same time, for those who know your back story, the references take on an added dimension.

CO: If people do know my story, it's even better because you see there's an effort being made to do the right thing, in my opinion. Who knows what the right thing is? [laughs] The ideas that are presented essentially become forgiveness and love instead of hate and angst. I mean, there's a song called "Forgiveness" on this album, too.

Pitchfork: On "Just a Song", you sing about how "it seems like nobody's happy now." Are you talking about a specific malaise or something more general?

Pitchfork: On "Just a Song", you sing about how "it seems like nobody's happy now." Are you talking about a specific malaise or something more general?CO: That's my favorite song on the record. There's a heavy point to that song, which is about an element of joy that has gone away. I don't want to whine, but there was something beautiful about our little [San Francisco] scene that we had when we were all in the gutter together. And now Sandy Kim, who used to take all of our photos, is in New York. And ["Hellhole Ratrace" director] Aaron Brown is making music videos for tons of bands. Everybody's doing what they want to do, but that whole family, that little thing that's very important to me, is gone. The song is very sad but it becomes hopeful at the end, like they all do, because the idea of creating your own happiness is presented.

It's saying, "Love is just a song." If you wanted a song, you could just find one, write one, you could get that. And love is something you can make, too, and you don't have to get it back from somebody. I can just love the hell out of someone, and it's just as rewarding as if someone was very much into me. Like, I love Gene Kelly, and I can watch him on DVD whenever I feel like it. It's a wonderful thing in my life and it's real love.

So many people wait around for love to be found for them, for somebody to say, "I love you." But sometimes it's just as much fun to love somebody that doesn't even think about you or talk to you: She doesn't have to love you back, you can just think she's neat, and that's fine.

And the line about keeping my feet on the ground is about drugs. "Just a Song" is the most personal one on the record. It's the closest to what I feel right now. I struggle with an addiction to serious, very heavy opiates, which is the reason I'm sick right now, because I'm cleaning up for the tour. I have to get clean, otherwise I have a bad attitude, or I'm looking for it all the time, or I get sick on the road and I'm bad during the promo, which is not acceptable. I've done this for every tour. Getting rid of this shit is literally the worst hell you can imagine. I don't know why I always go back to it, but I do. It's a big deal to go through, very serious stuff. And that's what that song's about, and I love it.

Pitchfork: What about the idea that the drugs fuel your art-- is that bullshit or is there some truth to it?

CO: It fuels the music in a very serious way. It allows you to focus on one thing-- I can pinpoint an idea or an emotion while very heavily medicated, which is how I write most of my songs. This is a reoccurring theme. All of my heroes have this same exact problem, except maybe Randy Newman-- maybe that's who I should be hanging out with. I think he and I would have a good old time, two pianos back-to-back.

No comments:

Post a Comment