5-10-15-20 features artists talking about the songs and albums that made an impact on them throughout their lives, five years at a time.

"Maybe I'm inventing this for your piece, because I don't remember nothing," says

Spiritualized's Jason Pierce with a laugh, talking about a foggy childhood memory. But, curled up with his knees to his chest in a spacious suite in Manhattan's Ace Hotel earlier this year, the supremely soft-spoken 46 year old talks about the harmonious voices that affected his life most with a far-off reverence that's anything but false. He might not be so hot on exact dates-- and he couldn't quite come up with anything for age 10-- but his brain isn't nearly as shot as he claims. Whether he's recalling the record player he grew up with, or the first time he saw Iggy Pop, or his initial introduction to gospel music, the details are sharp in all the right places. (Listen along with Pierce's picks on

Spotify.)

There's an English tradition where you watch people miming along to songs on "Top of the Pops" as a kid, and it makes you want to be a pop star. But I never saw that program at all when I was young. We didn't have a TV for long periods of time. Even now, I think, "You watched people fucking mime, and it made you want to become a singer?" It seems odd.

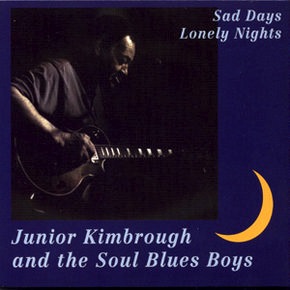

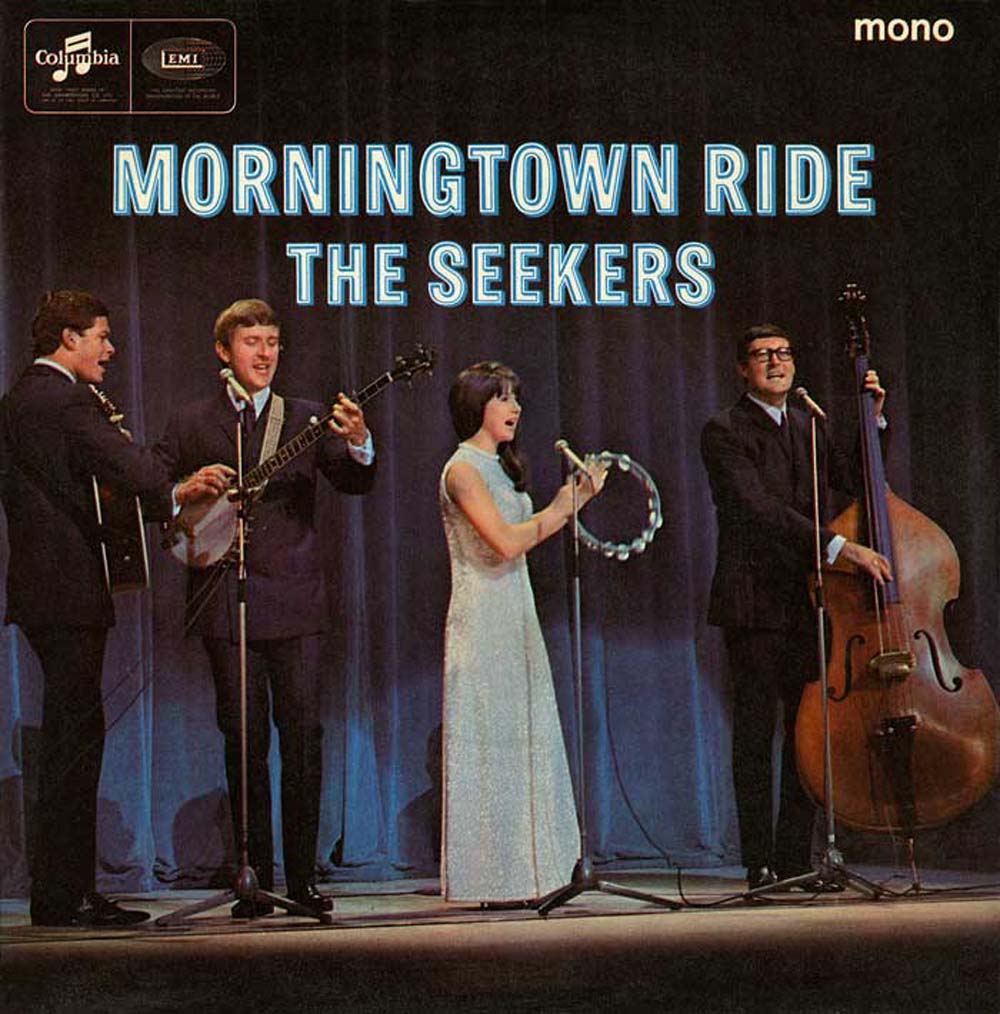

We didn't have much music or much money in our house growing up. But we had a record by the Seekers, who are essentially a vocal harmony group from Australia; by my definition, there's not a massive difference between

the Beach Boys and the Seekers. My father was gone by then, so it was my mum's record. She must have had about four LPs, including one by

Barbra Streisand that one of her sons bought her for Christmas because they didn't know what to get her.

With the Seekers, the harmony appealed to me. It's in the word: "harmonious." You can't distort it. That appreciation is in everybody. You never hear people say, "I've had [free jazz artist]

Peter Brötzmann going round and round in my head all day." Now, when you hear music that was made before what we recognize as a modern scale was invented, it sounds fucking odd. But at one time, when people heard that, they must've thought, "This is right. This is what music sounds like."

I remember our stereo-- it was wooden with a little plastic top on it. But I don't remember a time when somebody put on a record and played it until I got old enough to do that myself. We didn't sing; we didn't have a piano. Until my brother got old enough to buy a

Clash or

Sex Pistols album, my mum's four records were pretty much it. So I listened to the Seekers from day one, until I left home at 16.

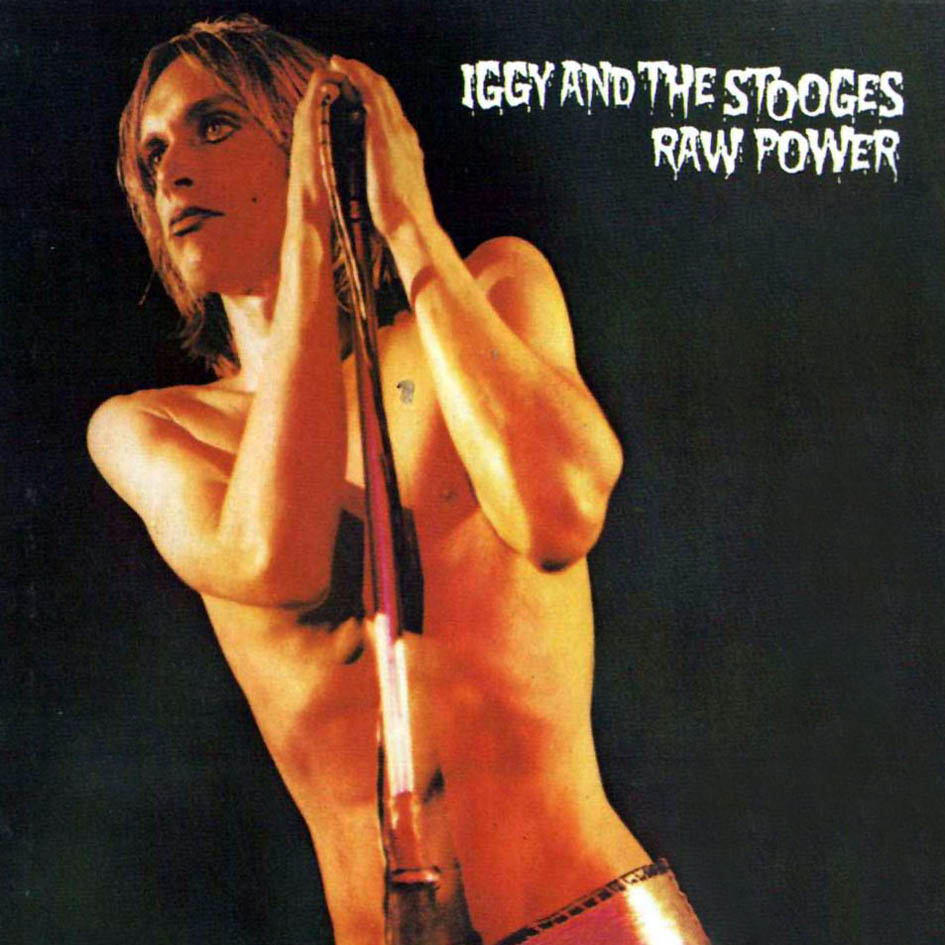

In the 70s, the English pharmacist Boots used to properly sell records. They had A-to-Z racks like you'd find in any record store, alongside hair products, toothpaste, deodorant. And I remember thumbing through those records in there and seeing

the Stooges'

Raw Power, which had Iggy with this wildcat jacket and leather pants. I bought it. I don't know why. I felt fucked up-- not fucked up like drugs, but just alien. Not like everybody else. I saw this album and thought, "That's for me."

It's a massive, amphetamine-fueled record-- but I didn't know any of that when I bought it. It was just random chance. I could have quite easily bought

Devo or the second Seekers album. But Iggy had silver hair and silver pants, and something clicked. Maybe it was on sale. I got lucky, because my whole life premise and what I do is kind of built around that record.

"Raw Power made me feel fucked up-- not fucked up like drugs,

but just alien. Not like everybody else."

Nobody knew the Stooges then: "Iggy Pop, who the fuck is that?" When you're a teenager, you're possessive over the cut of your clothes or the way you walk, and Raw Power felt like my discovery. I played the album to death. The good thing about records at my house at the time was that there was no competition. [laughs] It was like, "What do you want to listen to? We've got the Stooges and the Seekers." I knew every little noise on that Stooges record-- you play something every day for half a year and it becomes part of your blood.

I realized music was going to be a bigger part of my life when I realized that I had to get a job. And doing music seemed like the best thing you can do that isn't like working. It's an escape from your small town in England. At 16, I moved out on the day I left school and went to college for a year. I wanted to go to art college, but what I wanted more than anything was the grant. At that time in the UK, they would pay for your education-- they'd give you £1,500, and it was like free money. You were supposed to attend the college, but I came to an agreement with them that, if I stuck out the first term, they wouldn't say I wasn't attending and I could keep the cash. So I did a term, bought my guitar, bought my amp. I still own them to this day.

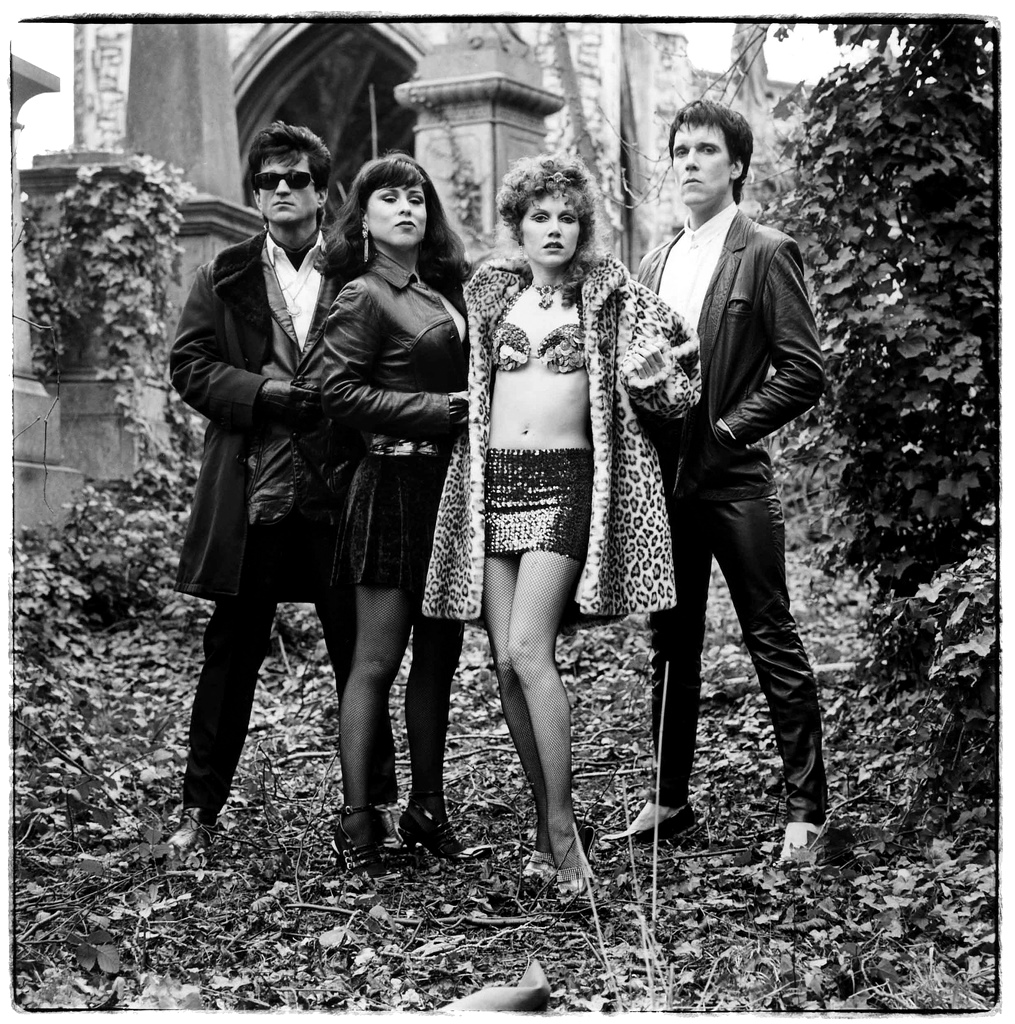

The idea of entertainment in most small towns is to go up to town on a Friday or Saturday night, get drunk, look for girls, fight, get drunk again. And the alternative to that is getting together in a room and playing music, two, three, four times a week. Making noise. It doesn't even have to be good. I don't think any of us were talented. But at this stage we were listening to

the Cramps, the Gun Club-- this very primitive sound. As soon as you pick up a guitar, you realize it's not complicated-- it's about hitting that chord over and over with some kind of venom and passion, like it's the most exciting thing in the world. And it

is when you're a kid. Most of the greatest music is made by kids, with the stupidity, arrogance, and single-mindedness of youth. It's like throwing stones and messing up your floor. It's the most exciting thing ever.

The Staple Singers

The Staple Singers

We had a little club where everybody came together in our town. Maybe it was over a fondness for drugs. Or just a fondness for a similar kind of music. But everybody seemed to be a bit more connected there. I lived with a guy called Natty [Brooker], who was the first and best drummer with

Spacemen. When he was a kid, he taped a lot of radio shows by

Alexis Korner, who would play a lot of blues and jazz and soul. A lot of it was stuff I'm not interested in-- white English blues players like

Eric Clapton-- but amongst all of that, there was a track by the Staple Singers. I'm not talking about Stax-era Staple Singers, but the sacred music they made prior to that. It was the first time I'd heard gospel music. I wasn't even in the room where it was playing on the radio, but I remember the sound coming out of Pops Staples' funny little tremolo guitar. And they had that harmony thing again-- it's like the Seekers for adults.

Around when I heard the Staple Singers, they had just started to reissue a lot of early gospel groups like the

Five Blind Boys of Alabama and the

Swan Silvertones, and that became really important. It wasn't all about the Stooges or

the Velvet Underground for me anymore. But, eventually, you soak it all up and figure out that gospel, country, the blues, rock'n'roll, and rhythm and blues are all connected. It all becomes one music that unlocks the same things inside of you.

"I've never been and will never be religious, but as soon as you have a conversation about Jesus, you know what you're talking to him about: how it is to be fallible and question yourself and your morals."

I get asked quite often about why I have references to the lord in my music. I've never been and will never be religious, but as soon as you have a conversation about Jesus, you know what you're talking to him about: how it is to be fallible and question yourself and your morals. Like on my

new album, with the line, "help me, Jesus"-- you know I'm not asking for help fixing the fucking car. You know there's a certain place you'll get to before you'll ask for that kind of help. It's like an immediate shorthand to the nature of the song. I would maintain that most of the gospel references in music-- aside from gospel music plain and pure-- have got little or nothing to do with the church. The church might say that as soon as you turn it into a popular-music thing, you devalue it. But in an odd way, it becomes so much

more powerful. How can the church own music anyway?

I always thought my references to the lord and Jesus came from gospel music. But then I realized the other day that, in doo-wop music, the lyrics to those songs tend to be like, "I pray to the lord above, he sent me an angel." All that lyrical content that I've always thought came from the Staple Singers is all in groups like

Dion & the Belmonts,

the Dixie Nightingales,

the Chantels-- the whole thing is built around that. Sometimes you just say things really simply in songs, like the way children write. People are like, "Don't say that, it's too simplistic, it's too embarrassing." Most people try to be more eloquent, or cleverer with language, but it cuts deeper because you've said it simply.

I always wanted to put out a record with

Fat Possum [co-founder] Matthew [Johnson] because it seemed like he's a guy that could find music that it is fucking scary and essential, like Junior Kimbrough, who was in his 60s, and was suddenly like, "I'm going to make a record." I like the fact that blues records like this, which came out in the 90s, still exist, and that they weren't all from the 20s through to the 60s.

It's really, really essential that you make new music. There's a whole industry now where people leave an album for 10 years and then hail it as a classic and then you can tour that for the rest of your life. When I was a kid, there were like Motown revues and, as much as I like Motown, the idea of going to one of those showcases where they played only old songs is just something I wouldn't do. I'm as guilty as the next man-- I did a few

Ladies and Gentlemen shows, and there's a lot of money to be made if you're tempted. Those

Ladies and Gentlemen gigs drove me to think, "Well if I'm going to make music now, it better be fucking good." But to be honest, even if it was awful, I'd much rather be making awful music that was new than just churning around old stuff.

Everybody wants a new style of music, but that's like trying to invent a new animal. Like: "Here it is." And you go, "Fuck, what's that?" It's almost impossible to invent something because it evolves so slowly. And quite often what people perceive as radical change in music is just a broad stylistic change or re-appropriation. With that as a given, it's important to go in the right direction and to making new music now.

"I'd much rather be making awful music that was new

than just churning around old stuff."

I've got this list of records that's like the spine of rock'n'roll-- records that are made by people with a bit more wisdom-- and

Royal Trux's

Accelerator is on there.

Neil Hagerty is an absolute fucking genius. I don't think I've got any bad recordings by the guy. Everything he's done since seems like it's just rolls out of him, and that's incredibly difficult to do, and for the songs to be that good. When you meet people like that, you think they've got this hotline where they can roll off another song, but I'm sure it's as difficult being Neil Hagerty as it is being the next man. But sometimes I get envious of that effortlessness because I have to work so fucking long and hard at what I do. "Stevie" is one of the greatest songs ever written. It's produced so fucking weird, like it's all just been squashed.

The MC5 always talked about

Sun Ra, who introduced me to a whole world into free-form music. There's moments of that on my new album, but it's almost like you're having your hand held and led in there, and you leave a trail of stones so people can get out. It's not like being dropped into this furious abstract world. And I think the same can be said with Sun Ra. It's abstract and free, but also based around melody.

I saw the Arkestra-- admittedly without Sun Ra, but with Marshall Allen-- twice during the last two years, and they were by far the best shows I've been to in the last 10 years. There's a little club near me where there's no stage, so you'd be 10 feet away from this band playing this extraordinary music. Also, it's as strange as Iggy in his silver pants, in a way, like they really have just dropped in from another planet. I like the mythology of rock'n'roll, and the very cornerstone of that myth is that Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads. Which is like, "Give me a fucking break." But I'm a sucker for it. So I love how the Sun Ra Arkestra is 3,000 years old, and all the space-traveler stuff. It's the best thing in the world.

I haven't been into much new music because I've been making a record, which ruins my enjoyment of music because I can't listen to anything without listening to the production value of it. It's like if you make films, you start admiring the way a scene's lit or edited. When I'm making a record, I start listening to the way people have positioned the snare drum in the mix. So I can't listen to anything. In fact, the only thing I've been known to listen to of late is the The Smile Sessions box set, because it's like the sound of somebody else making a record.

I still feel like I'm hustling, and like I have no great talent. I'm not a great singer. But as long as I can keep the hustle going, and nobody taps me on the shoulder and says, "You're busted," then I can keep doing it.

The Seekers:

The Seekers:

The Staple Singers

The Staple Singers